This is not a post about programming; rather, it’s a reflection on the philosophy of aging, framed through the lens of gym culture and enriched with training insights. It’s a success story tinged with a hint of remorse. Note: it includes an image of a bare-chested teenager, so it might be considered NSFW—your call.

Introduction

Briefly, I’m a male in my thirties, 185 cm (approximately 6’1”) tall, and weigh 80 kg (around 176 lbs). During my teenage years, I was heavily into calisthenics and considered myself stronger than the average teenager at the time. Back then, it was a necessity: growing up in a bleak neighborhood of a depressive city in a depressive country meant that violence and physical force were the primary means of conflict resolution. Giving up the fight would mean being consumed by misery forever. Looking strong also served as an effective deterrent to conflict in the first place, making it an essential priority.

Me at 16 years old. Sunbathing.

Life is a stream that takes twists and falls, so my adulthood took a twist too. I got to move to another town when I was 19, and combining full-time work with full-time education squeezed all the energy out of me, and sports pretty much ended for me. I tried to regain my strength by going to the gym again, yet the deceptive “I have more important things to do” would push me out of morale within the first month after starting. It carried on with subsequent immigration, learning new languages, changing careers, etc. The adult, professional life required no physical strength but much more intellectual and interpersonal strength, so my body embarked on a decadence ship, sailing over a decade into the future.

Some pills are tough to swallow, and aging uncovered that my philosophical perception of death and destruction has a clear boundary drawn across death metal songs. I have been clearly unprepared to age.

Not like I woke up overweight, but I was evolving into a “dad bod.” My chest started to sag, and my belly erupted from my, not so long ago, young body. One day I just saw a picture of myself and understood that I was on the path of decay and wanted to fight to slow it down.

Gaining the motivation

The challenge with sports is that it takes time to see tangible results—often longer than most people are willing to stick with it. This was a major stumbling block in my previous attempts, so I started this journey fully aware of the issue. This time, I equipped myself with an app to meticulously track every set I performed, including repetitions, weight, and set count. I personally used “Strong” app, which I found excellent, but even a basic spreadsheet can do the job. I’ll be sharing a lot of data from Strong because I used it extensively, but this isn’t an ad, nor do I have any affiliation with its creators.

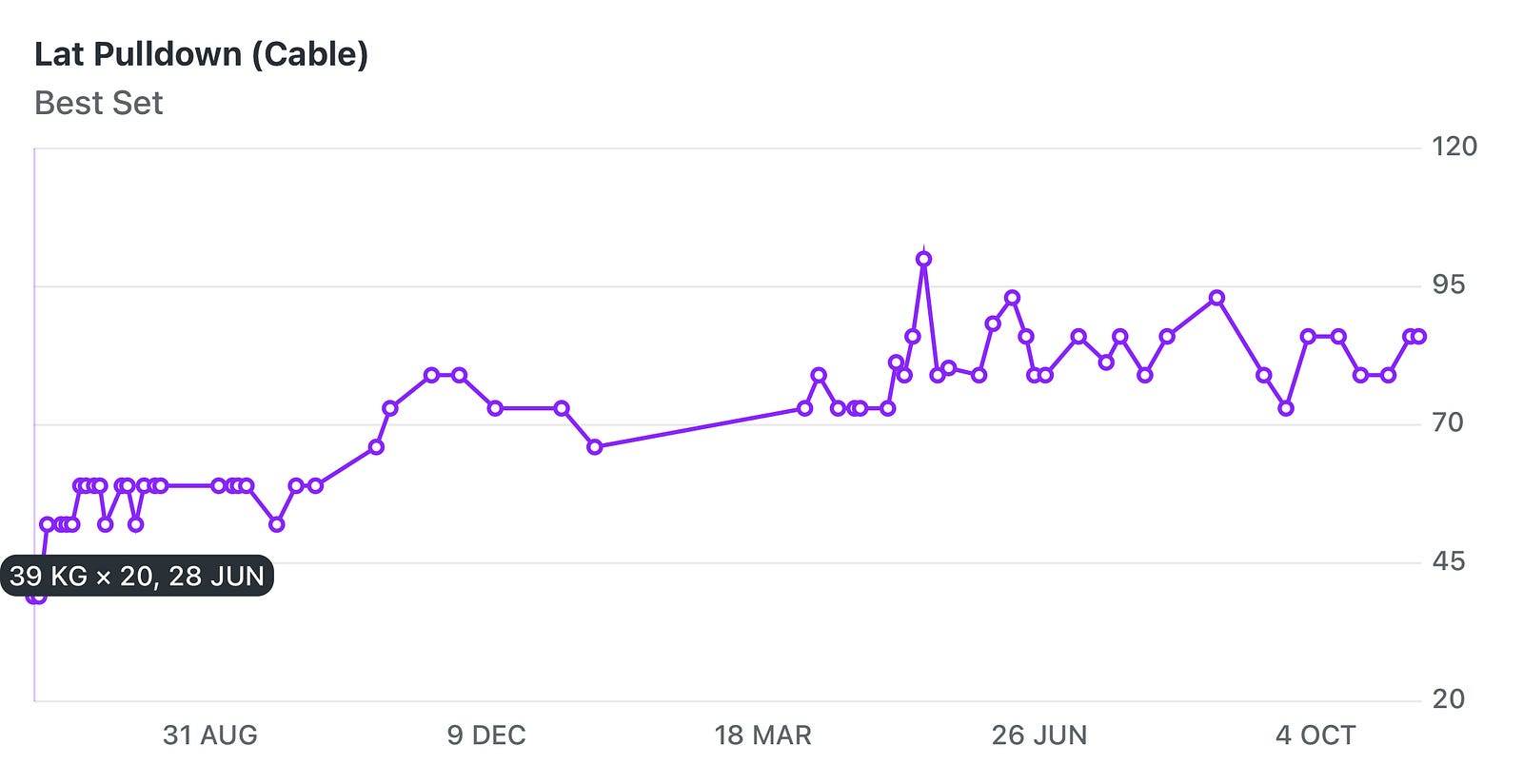

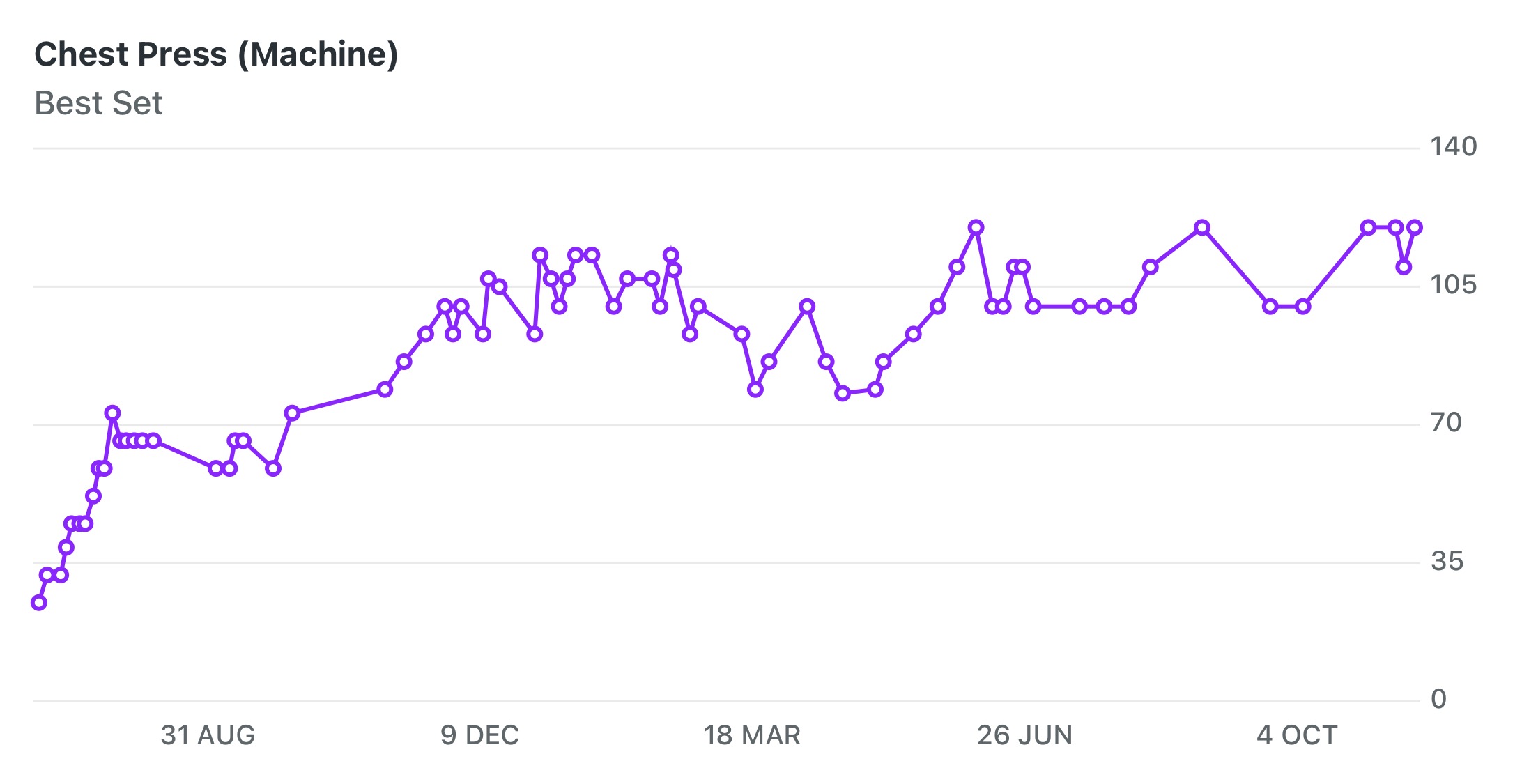

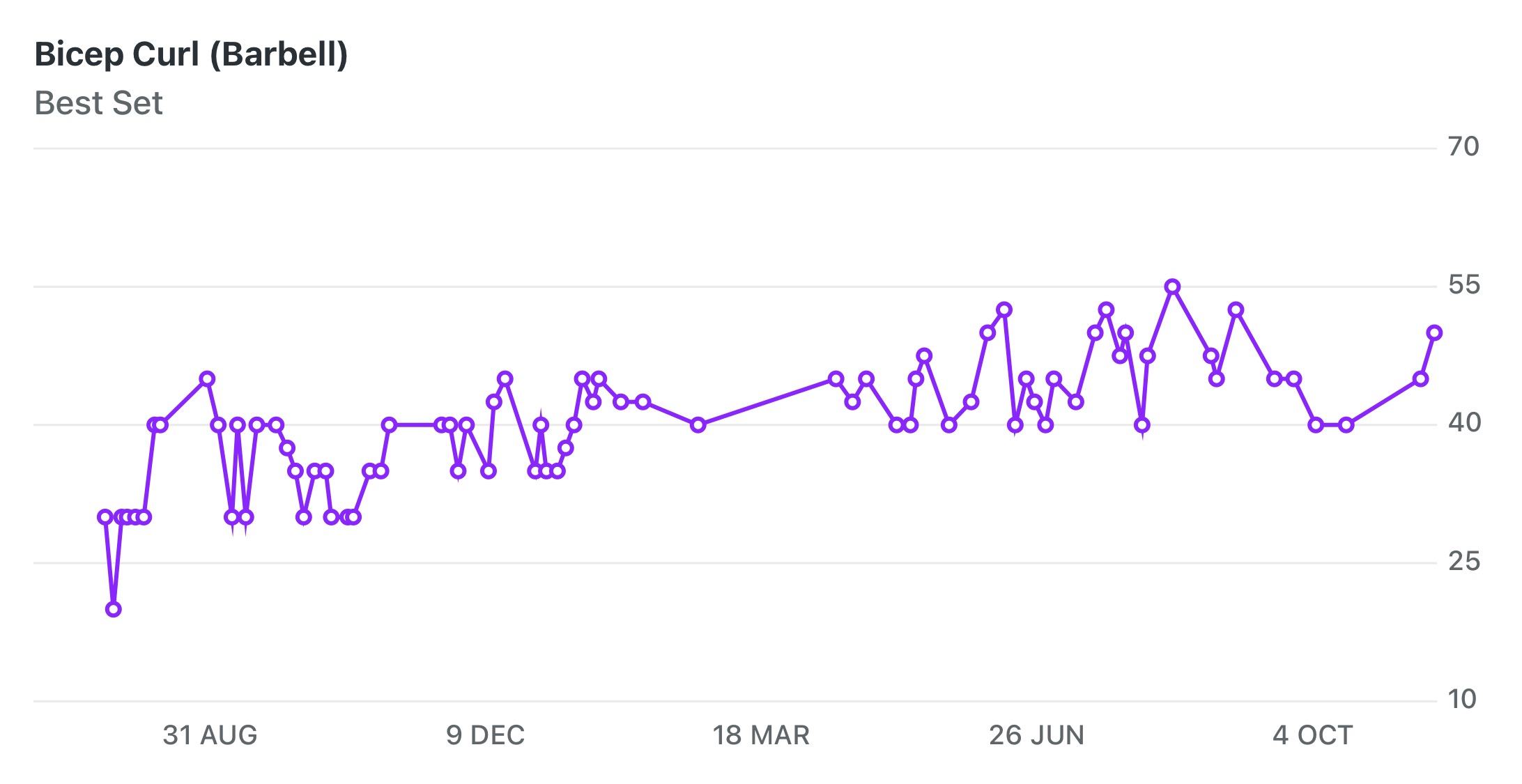

My first discovery was that, in the early stages of training, your muscles show significant progress in the power they can exert, even if this progress isn’t visible in the mirror. At this stage, your muscles are essentially “getting in tone.” I observed this early spike consistently across various exercises throughout my journey, regardless of how late I started targeting specific muscle groups (for example, I was late to start training shoulders—but more on that later). A new type of exercise almost always resulted in daily progress early on. Having data from my previous sessions readily available was incredibly motivating; it tapped into my competitive nature and pushed me to outperform my previous attempts.

Here’s a concrete example: I progressed from 10×39 kg (86 lbs) to 10×59 kg (130 lbs) in under a month. This wasn’t due to muscle growth but rather to my muscles becoming more tuned and efficient.

But also, interestingly enough, it’s the fastest growth you’ll ever have (well, at least in my case).

Routine

I go to the gym 3 times a week. I’d go more if I could, but adult life is busy, and I simply can’t make more time for it. I focus on specific muscle groups every day, with the upper back and chest being most frequent, and legs being the least frequent. My goal is to focus on the heaviest weight that I can push/pull/squeeze 10 times per set. I do 4 sets of each exercise with 1–3 minutes rest between sets. On a bad day, it may be less than 4 sets or less than 10 reps in one set. I simply push myself as hard as I can until I can’t do it anymore. In one go, I do 3–4 exercises, which takes roughly an hour. It was more when I was starting because of less weight and shorter rest time. But after a 120kg chest press, I simply don’t recover in 2 minutes anymore. It also burns enough energy to make it difficult to do more exercises in one go.

I found that my performance is 20–30% better when I listen to metal music than without it, probably because it helps me burn through inner anger and frustration and push harder. In general, going to the gym angry is very good for setting personal records, and as a side effect, it also helps to express less aggression outside of the gym.

It’s probably a hot take, but I think you need to be aggressive to get results. I’m seeing folks who are doing everything methodically (which I deeply respect, don’t get me wrong), and they’re not getting anywhere. There’s some anecdotal research that connects anger to increased testosterone levels and decreased cortisol levels, which seems to be true, at least for me.

The modern world doesn’t reward aggression and masculinity, and I think that having a place where you can express it is very therapeutic and helps me retain sanity.

Trauma

When middle-aged, you can think about exercise as a battle against your own mortality. I was surprised to hear from my friends that it’s not only me who thinks this way, and perhaps there’s some deeper psychology that could explain this motivation. And just like in any other battle, sometimes you win, and sometimes you lose and get wounds. I found myself traumatized much more often than I did in my teens, which is yet another reminder of time and the built-in self-destruction that will inevitably lead to eventual death.

Some of the traumas are minor and go away over the course of a week or two, while others… may stay forever. Traumas are major setbacks as they prevent you from exercising the damaged part of the body, and in some cases, you may need to take a break from the gym altogether.

A good example is my progress with the back extension machine. The lower back can squeeze with a lot of force, allowing you to push a lot of weight, and you progress really fast. But when you return to the initial position, you have 120–160 kg of weight pushing you down, which eventually led to a tailbone fracture, limiting my ability to sit for a month, let alone exercise.

It’s also important to maintain a balance in your muscle growth. I developed severe shoulder instability by overtraining my chest and not training my back enough. It’s a common mistake, as the chest is a much stronger muscle group, and you can push a lot more weight with it, while the back is a much weaker muscle group, and you can’t really push as much weight with it. It’s also a less visible muscle group, so it’s easy to forget about. I wasn’t able to bench press or do heavy shoulder exercises for months, and my shoulders still have limited mobility compared to what I had before.

All of those breaks set you back. I find a week of sickness sets me back for a month. COVID was especially bad, as two weeks set me back by 2–3 months. It’s a long journey, and you need to be prepared for setbacks.

As advice to everyone—find a good physiotherapist and listen to them. They can help you avoid a lot of problems and recover faster. I should have done it sooner if I were smarter.

Form

Shitty form helps you start faster, and it’s what makes you feel quicker progress. Therefore, it’s so attractive to ignore advice and just do your own thing. It’s a slippery slope because you don’t feel the negative effects on smaller weights but eventually end up traumatized and/or plateauing.

In most of my exercises, I’ve found myself reaching the ceiling of what I can do with the wrong form and then dropping a quarter of the weight while trying to achieve better form. There are still a bunch of exercises where I could manage more weight with poor form, which is a challenge that trains your acceptance of taking a loss. Yesterday you could do 100 kg, but now it’s only 80 kg, and you need to regain your records with proper form. It’s a humbling experience and a good lesson to learn.

Yet, for other exercises, form helped me overcome a plateau and reach a new record. I’ve had encounters with trainers, but I never found a person I’d click with. Often, I struggle to understand their advice, which makes me feel angry and consider them unreasonable. I wanted to find someone who’d tailor a program around my current abilities but never did.

I’ve found a lot of good advice on the internet, and I’ve found a lot of bad advice on the internet. It’s a good idea to cross-reference and try to understand the reasoning behind certain ideas. If you can’t understand it, it’s probably not for you, and you should look for other advice. YouTube videos are good because you can visualize the exercises and then try to polish them in front of the mirror.

I’ve read books, most of which eventually turn into advertisements for proteins and other supplements, so I can’t recommend many books besides “Bigger, Leaner, Stronger” by Michael Matthews. It’s a good book, but it’s also an advertisement for his own products, so take it with a grain of salt. This specific one has been helpful in establishing a good routine.

What you eat

So, shortly:

- You need to obtain protein, one way or another.

- You need to obtain energy, which means you need to eat carbs.

I don’t do supplements, not even protein shakes. Instead, I exterminate the population of free-range chickens monthly and eat at least 4 eggs daily.

On its own, increased consumption of meat isn’t ideal philosophically, so I try to offset it by buying only free-range meat to ensure my prey is respected before it’s killed. I tried eating vegetables and meat alone but lacked the energy to push through exercises. So, I ended up eating whatever I want, just making sure I get enough protein and energy. I do not keep track of my calorie intake. I tried, but it feels like a waste of time, and I don’t see any benefits from it. I don’t have visible abdominals because of that… but you know what? Screw it, I’m fine with that.

I tried to do a proper cut… and failed miserably. I lose my strength when cutting, and I don’t feel like I really want that.

Plateau

Eventually, you plateau, and all progress becomes very minor, if any. I can go for weeks without setting a new record anymore, and it takes a toll on motivation. A fear of losing progress was the only driving force on some of the harder days, which is still a motivation nonetheless.

There’s research that claims we can’t naturally increase our muscle mass by more than 20–25 kg (40–50 pounds) over our lifetime, and there are even calculators for this. I think if you start in your thirties, this number is substantially less than that. I imagine I’ve probably swapped around 10 kg of fat into muscle, but it’s unlikely to be more than that.

The same applies to your physique. I’ve had people tell me that I looked jacked after ~9 months of regular exercise, and my personal opinion is that I reached my current form after 12–14 months. Afterward, I’ve just been maintaining it and trying to push a bit further, but it’s very slow progress, if any. I feel like my muscles are becoming more refined but not really getting bigger anymore.

Understanding the ultimate limitations of myself is another humbling experience, which I’m honestly not handling very well.

Conclusion

Do it—you won’t regret it. I’ve learned a lot and will probably learn even more moving forward. I’m happy with where I am now and excited to see what’s ahead of me. Let’s wrap it up with a silly selfie from the gym changing room to showcase the results and the stats:

Maximum sets as of November 2024

(10 reps, not 1 rep max):

- Chest press machine: 120kg (265 lbs)

- Bench press, barbell: 80kg (176 lbs). Well, I did 100kg (220 lbs) 5 reps, but can’t flex 10x yet.

- Pulldown: 86kg (190 lbs)

- Shoulder Press: 74kg (163 lbs)

- Seated cable row: 79kg (174 lbs)

- Seated diverging row: 89kg (196 lbs)

- Leg press: 180kg (397 lbs)

- Bicep curl: 55kg (121 lbs), but with a proper form it’s only 50kg (110 lbs)

- Pectoral fly: 89kg (196 lbs)

- Lateral raises: 18kg (40 lbs)…

- Back extension machine: 160kg (353 lbs)

- Deadlift: 80kg (176 lbs). I’m too scared to push it, as it’s quite dangerous until I’m confident in my form.

- Arnold press: 44kg (97 lbs)

- Tricep pushdown: 60kg (110 lbs). Beware, it’s a cable machine, and it’s definitely lighter than free weights.